I n sleepy, suburban Saugus, Massachusetts, sisters Robyn D’Apolito and Nicole MacTaggart pack up the car, getting ready to meet about 30 members of their friends and family at Castle Rock Park in Marblehead. It’s July 2022, high season for the New England shore, but this isn’t a typical trip to the beach. The sisters are on their way to scatter the ashes of their mother, Adele Mazzone, at her favorite place: where she used to sit with her toes in the sand, eating ice cream, while her kids scrambled over stony outcroppings as the waves crashed below.

Before heading to the sea wall, D’Apolito carefully sets up little plastic condiment containers in the back of her car, pouring the fine gray ashes into each. Then she passes a cup to each mourner, all dressed in white for the occasion. This was Mazzone’s last wish, to be laid to rest at sea. One by one, they pour their portions into the breeze. A peaceful final goodbye.

“It was a beautiful day,” D’Apolito tells me.

After Mazzone died three years earlier at age 74 of complications from a stroke, her remains had been handed over to Harvard as part of the Anatomical Gift Program, a donation-based initiative in which people can leave their bodies to the school for students to use during their studies. Harvard Medical School is among the top in the country — it ranked Number One for research in 2023 — which means Mazzone’s selfless last act would help to train the future of American medicine.

“Since we were little, my mom would always say, ‘I want to go to college. I’m going to Harvard,’” D’Apolito says, fiddling with the pages of Mazzone’s journal, full of musings and prayers for her family. Her mom never got the chance to go on to higher education, despite being a voracious reader and having an endlessly curious mind. Still, she was from Massachusetts — so, for Mazzone, there was no more revered institution than Harvard.

Adele Mazzone always wanted to go to Harvard, but never got to go to college. “She was raised with the values to idolize Harvard, the esteemed university,” her daughter Robyn says. “I just think she’d be so disheartened to know the lack of professional integrity that Harvard now stands for.”

On June 14, nearly a year after that summer night they had scattered their mother’s ashes, MacTaggart turned on the TV. Harvard was splashed all over the local news. Cedric Lodge, the manager of a morgue at Harvard Medical School, had been indicted by a federal grand jury in Pennsylvania — along with several others — on charges of conspiracy and interstate transport of stolen goods. The broadcast went on to explain that those so-called goods were body parts from corpses donated to the Anatomical Gift Program — the very same program to which Mazzone had proudly donated her body.

“I was having a heart attack,” MacTaggart says. “I had no idea what was going on.” Her first instinct was to call the university, but it was nighttime. When she returned home from work the next day, there was a certified letter in her mailbox that confirmed her worst fears.

“We cannot rule out the potential that Adele Mazzone’s remains may have been impacted,” the printed letter read. “We are deeply sorry for the pain and uncertainty caused by this troubling news.”

Were those ashes — the ones they’d received in a plain black box in the mail from Harvard, the ones they’d so carefully divided up among their family members to scatter at sea, the last remaining physical presence of their mother — possibly not even their mother at all?

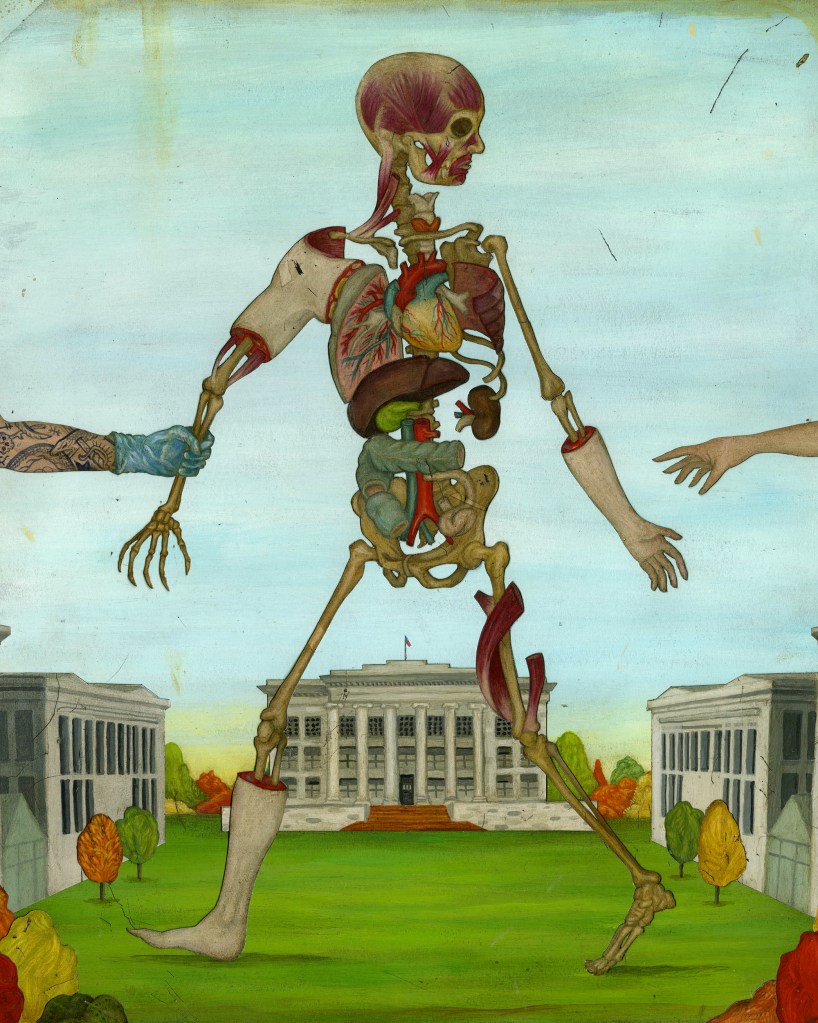

YOU COULD SPEND YOUR years on the picturesque grounds of Harvard and never think much of the block of medical buildings that house the morgue. They’re not those beautiful red-brick buildings with ivy crawling up the side — instead they’re marble, gray, and austere. The main one sits on the south side of the quad lawn, a stately piece of architecture framed with imposing columns and an American flag waving proudly on top, like a miniature version of the White House. You could pass right by the buildings every day and never give a thought to the fact that somewhere beyond those columns is where bodies go when they’re donated for dissection and study, and stored before they’re eventually cremated.

Once a body is given over to Harvard, that’s meant to be its final destination, where various parts are studied by Ivy League students suited up in surgical gowns and latex gloves. Future doctors and dentists work carefully on their assigned embalmed cadavers, learning about, say, the collection of nerves in the upper arm, or the tiny ligaments and bones that come together at the knee. They’re taught and tested and trained, and the donor’s ashes are usually handed back over to their family, their final sacrifice complete. The donors are generous people like Mazzone, who opted to give up traditional burials in the name of science.

When a grieving son or daughter hands over their loved one to Harvard, they’re trusting the storied institution to handle them with respect. They’re passing over their parent or grandparent believing that they’re in safe hands with the academy.

Paula Peltonovich’s parents, Nick and Joan Pichowicz, donated their bodies to Harvard after their death. Only Nick, though, is a potential victim. Paula says of her father, who served as a deputy sheriff and opened his home to several foster children. “[My parents] were caring people; they wanted to give back.”

But in 2018, the unthinkable happened. Lodge, the longtime manager of the university’s morgue, and his wife, Denise, a former New Hampshire state government worker, allegedly started selling pieces from those donated bodies. The imprimatur of the Harvard morgue — the official procedures, the sterile facilities — became twisted and entwined with a dark corner of the world of oddity enthusiasts, people who collect out-there specimens. Donors were traded like baseball cards. And for years, family members, who thought their loved ones were laid to rest, were none the wiser.

MORGUE MANAGER CEDRIC LODGE and his wife haven’t spoken publicly since their arrest — Cedric’s lawyer declined to comment, while Denise’s did not respond to my request — so we’ll have to go off the indictments to explain what allegedly happened in that morgue over those five years.

Lodge — who, along with his wife, pleaded not guilty — allegedly allowed people to secretly come into the morgue he ran to pick out human remains to buy and take home. The customers were largely oddity collectors, people who buy strange things like medical equipment or taxidermy, and sometimes transform them into new creations like jewelry or figures. There’s a particularly macabre segment of the world of oddities made up of people who don’t just collect unusual knickknacks — but actual human body parts.

One of the Harvard morgue customers, according to prosecutors, was Katrina Maclean, who owned a store called Kat’s Creepy Creations in Peabody, Massachusetts. “I paint creepy dolls and play with dead things for a living,” Maclean, who also pleaded not guilty, said of her business in a 2021 podcast. Her store, now closed, sold figurines dressed up like haunted clowns, vampires, and other creatures — these dolls were sometimes made up of human bones. Another patron was Pennsylvania oddity collector Joshua Taylor, who runs a ghoulish Instagram account called Angry Beard Antiques, featuring photos of skulls, bones, and postmortem daguerreotypes of dead children. (Like his fellow defendants, Taylor also pleaded not guilty. His lawyer declined to comment.) Lodge and his wife also allegedly shipped remains across the country to buyers they had met on social media, and stored various body parts at their New Hampshire home.

Once the remains were furtively released from the campus to these collectors, they continued to travel, bartered and traded via Facebook messages.

This kind of oddity collecting has been around for centuries, capturing the imagination of folks throughout the world. And it’s mostly technically legal. Aside from the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which was established to repatriate Native remains from museums and federal agencies back to their families, there are no federal laws that prohibit owning human bones, Wake Forest School of Law professor Tanya D. Marsh tells me. And there’s also no federal law against the trade of so-called wet specimens — the repugnant term for non-skeletal remains. (There are eight states where the sale of remains is pretty broadly illegal, however, including Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Texas. The Lodges were charged by federal prosecutors — and not with any crimes on the state level.)

There’s “a whole group of people that find a kind of beauty in the macabre,” says Tonya Hurley, a founding member of the Morbid Anatomy Museum, a now-defunct nonprofit in Brooklyn that sought to educate the public on nature, death, anatomy, and the like through exhibits and talks. Institutions like the Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which was established in 1863 and sees more than 100,000 visitors per year, share that same goal. Mütter displays body parts in an effort to teach visitors about their own anatomy as well as medical abnormalities. And there are myriad oddity fairs and showcases that draw thousands worldwide. “It’s taboo to talk about death,” Hurley says, which is exactly why the study of remains can be fascinating to some. People in this community see it as an effort to lessen that taboo and demystify dying.

The Mütter Museum, the fairs — they may give some people the creeps, but they’re legally above-board. Though it’s not uncommon for bad actors to crop up in this world. “Grave robbing has been going on for centuries,” Hurley says. “The Harvard incident exposed the black market once again.”

Janet Pizzi remembers her uncle Michael’s kindness. He befriended a non-verbal child in his neighborhood, bonding over their love of the clarinet. The child played for Michael while he was dying. “My uncle was a really interesting and talented man,” Janet says of Michael, who worked in real estate well into his 90s. “He related to people, and he probably worked harder than anyone I know.”

And that’s what made the whole thing so shocking: that this happened at such an esteemed university — and that the alleged customers were seemingly purchasing these body parts as some sort of gruesome, underground hobby, and to turn a profit. These kinds of illicit sales are usually conducted by medical schools and programs that can’t afford their own bodies, says Dr. Thomas H. Champney, a professor of cell biology at the University of Miami. But these donors had opted to be part of the donation program and were passed along to nonprofessionals. “The oddity collectors through Harvard, it’s actually kind of the worst example of how it goes, because those people really have no reasonable rationale for owning or obtaining those tissues,” Champney adds.

Law professor Marsh agrees: “I was not particularly surprised that there was a network of people selling human remains in this way. I was a little surprised that they were being taken from Harvard Medical School.”

Harvard Medical School declined to comment, instead pointing me toward a statement on its website which explains that Lodge has been fired and that Harvard was unaware of his actions.

Lodge’s turn from respected morgue manager to alleged body thief was a shock to those who knew him. Lodge is known in his Manchester, New Hampshire, neighborhood as the guy who is “slightly eccentric at Halloween,” says his neighbor, Alan Palmer. But, in hindsight, many details of Lodge’s life do seem curious. There’s Lodge’s Facebook picture, which is a jack-o’-lantern, and his family car’s vanity license plate, which reads “Grim-R.” And then there are the Zillow photos of the Lodge family’s previous home, which they sold in 2020 before moving next door to Palmer; inside the purple-and-white Victorian squatted stone gargoyles and multiple refrigerators — including one in the bedroom.

But mostly, people who knew the Lodges describe them as quirky but relatively normal. “He was quiet, you know. He had a select group of guys that was like himself in school. He was into a lot of science-fiction stuff,” says high school classmate Kevin Garraway. “If you’re looking to see if there’s like a dark side to him or something like that, I’ve never seen it.”

His neighbor Palmer agrees: “I know a lot of journalists and news outlets want to hear ‘This guy was up all night running a chain saw in his basement,’ but it wasn’t like that.”

Lodge wasn’t the only morgue worker alleged to have been caught up in this operation, though — the stolen-bodies network extended beyond Harvard. Candace Chapman Scott, a mortuary worker from Little Rock, Arkansas, was also allegedly involved; she, too, pleaded not guilty. Scott’s mortuary worked, in part, with the University of Arkansas for Medical Services to cremate remains from its Anatomical Gift Program, as well as from local funeral homes. Scott’s indictment implies that she stole corpses from the program — the delivery of new bodies to the school often aligns with her sales to an oddities collector named Jeremy Pauley — but a representative from the school denies that its cadavers were involved. The school has since terminated its contract with Scott’s former mortuary. A lawyer for Scott confirms she’s in an Arkansas jail after undergoing a mental evaluation, and says, “We’re in the process of going through discovery.”

There’s nothing in the indictments that says Lodge and Scott worked together directly. It was Pauley who was allegedly the connective tissue between their dual black markets, often reselling Scott’s stolen body parts to other collectors, including Lodge’s “clients.”

East Pennsboro Township Police Department

THIS WHOLE TWISTED OPERATION might have continued had Sarah Pauley not ventured over to her husband Jeremy’s side of the basement in July 2022.

As she tells the story now, her blue eyes narrow. “‘Just stay the fuck out of there. I don’t want to hear you bitch.’ That’s what he said,” she tells me. “He was like, ‘Stay away from that side. It’s not your business. It’s not your stuff.’”

Sarah was only 21 when she started dating Jeremy after hitting it off with the then-35-year-old at his Pennsylvania vape shop. She knew he collected body parts — she thought it was kind of cool. He showed her pictures of bones and preserved specimens. “I didn’t know you could own stuff like that,” she says.

But the relationship quickly became troubled. Sarah tells me that Jeremy was abusive and she first tried to leave him in June 2021 — then came back to try to make the marriage work. After moving back in, though, she says, Jeremy became convinced she was cheating and threatened to cut her into pieces. (Domestic-violence charges were never brought against Jeremy, and through his lawyer, he says he never made that threat.) Sarah filed a temporary Protection From Abuse Order against him, and he was evicted from their home in June 2022. Which leads us to the day she went to Jeremy’s side of the basement.

There were empty specimen jars, Tupperware full of mysterious fluids, sloshing Home Depot buckets, and a faded picture of Jesus propped against a stack of boxes, watching over it all.

“I lifted the lid of a bucket and I knew immediately [that this was different] from his previous work, which was legit,” Sarah says. Jeremy’s specimens were usually antique, preserved in jars with labels explaining their provenance. But this looked like a bucket full of loose organs.

Sarah went back upstairs to eventually call the police, handing over everything she’d found in the basement, along with Jeremy’s laptop, which he’d left behind when he was evicted. On it, the police — and later the FBI — found that Jeremy had been allegedly buying and selling body parts, the center of a web of brazen bandits that stretched across the country.

JEREMY PAULEY CONNECTED with Scott, the mortuary worker in Arkansas, through a Facebook oddities group, according to an indictment. In October 2021, Scott messaged him: “Would you know anyone in the market for a fully in tact [sic], embalmed brain?”

He ended up sending her $1,200 via PayPal for two brains and a heart.

Over the course of their relationship, Scott allegedly sold Pauley organs, genitalia, and on more than one occasion, fetuses. Along with working with morgue employees, Pauley did business with other collectors. According to an indictment, Maclean, of the creepy-doll store, enlisted Pauley to tan human skin into leather, which, Sarah says, he often used to bind books or make wallets.

These horrifying details are stomach-churning. And while it may be easy to get distracted by them, forgetting about the real-life victims and their grieving families, each person has their own story — and it’s heartbreaking to think of them. Like the stillborn whose mother had named him Lux — Scott allegedly sold him for $300 to Pauley, who traded him to Minnesota tattoo artist Matthew Lampi (who was also named in the indictment and pleaded not guilty) for $1,550 plus five human skulls. After the loss of her child, a funeral home that had the haunting misfortune of working with Scott’s mortuary gave Lux’s mother a box of mysterious ashes instead of her son.

All told, prosecutors say tens of thousands of dollars changed hands in this gruesome years-long scheme: One indictment states that Pauley sent Taylor more than $40,000; Lampi paid Pauley more than $8,000; and Pauley paid Lampi more than $100,000. Sarah estimates that her ex made a couple hundred thousand dollars in total.

Those listed in the main indictment weren’t Pauley’s only “customers,” which means this network spread further than it seems.

Pauley was also online pals with a Kentucky man named James Nott, who in his Facebook messages to Pauley went by the name William Burke — a grisly nod to a murderer from the 1800s who sold his victims’ corpses to Scottish anatomist Robert Knox for dissection demonstrations.

Nott was nabbed by the FBI in July 2023, after agents reviewed Facebook messages between him and Pauley discussing bones Pauley was interested in buying. When they raided Nott’s home, which held a stash of weapons, he was only arrested for possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. His home was like something from a horror show, decorated with dozens of human skulls, spinal cords, and hip bones — but he wasn’t selling to the few states where such sales are prohibited. And, he insists, he wasn’t doing anything illegal.

In texts to me from Oldham County jail, Nott endeavors to distance himself from Lodge, claiming to have never received stolen goods from the Harvard morgue — despite the fact that after his arrest investigators found a Harvard Medical School bag among his belongings. Nott also stresses to me that he only collects bones, not organs or body parts. It’s a distinction that does little to alleviate the horror victims’ families felt when they read news stories about Nott’s arrest.

Lilli and Ellen’s grandfather, William, was a Harvard-educated pediatrician with a special empathy for children. “I was bullied terribly, starting in fourth grade, and my grandpa was my confidant,” Ellen says. “For years, he would call me once a week.” William was also famous for his carrot cake, which his granddaughters refused to eat when they were kids. He made bowls of cream cheese icing for them instead.

As I spoke to those families over the past several months, the same question came up again and again — a question I, too, have grappled with as I pieced together this story. Why? Why would the people trusted to take care of these bodies risk their careers? Why did they betray that trust? And why, exactly, would anyone be willing to cause this kind of pain in pursuit of a grisly hobby and extra cash?

As for Cedric Lodge, it’s unlikely we’ll have an answer to that question until the trial, which begins in April. And none of the other main defendants are talking, given ongoing investigations and litigations. Lampi’s attorney declined to comment on the case — although he did tell me that in 39 years as a criminal lawyer, he’s never seen anything like this situation. Maclean’s attorney didn’t return my request for comment.

But for Nott, at least, he claims that his collection is meant to honor the dead rather than desecrate them. He tells me that he started collecting his “dead friends” after a friend died by suicide. “All the pieces I have collected, I’ve kept on antique furniture and placed roses and flowers around them and gave them their own names, as if keeping them alive,” he wrote to me, adding that his fellow prisoners call him “the Bone Man.”

As for Jeremy Pauley, the alleged linchpin in this shuddersome saga, Sarah says she believes her soon-to-be-ex-husband did it, in part, for the money. But she says of Pauley, whose website is still active, emblazoned with a photo of the man in a dark suit, face half in shadow: “He definitely didn’t have a moral compass.… He’d be like, ‘This is from a murder victim.’ He would know the story behind [the bodies]. But he’d cut shit up like it was just another Tuesday.”

About one year after Sarah descended her basement steps, the Lodges, Taylor, and Maclean were indicted on June 13, 2023, for conspiracy and interstate transport of stolen goods; Pauley was indicted a day later in a separate filing. Scott was indicted a few months earlier, in April. Pauley took a plea deal, pleading guilty in September 2023 to purchasing “human remains from multiple individuals knowing that those remains were stolen [and] selling many of the stolen remains to others, at least one of whom also knew they had been stolen,” according to the Department of Justice. He faces up to 15 years in prison. Scott is scheduled to go to court in March 2024. And Nott changed his plea to guilty in November 2023.

A report promising to assess the Harvard Medical School donation program to prevent future thefts has been delayed twice, with no word on when it will be delivered.

AS FOR THE FAMILIES, they want to remember the people they loved before they became “goods” to barter and sell — and they want the world to know them, too. That’s why after the news broke, many turned to the legal system, suing Harvard and the others involved in an effort to make sure that the memories of their fathers, mothers, and grandparents didn’t get lost.

Amy and Jenny Gordon remember their mother Doreen Gordon’s macaroons, one of the confections that earned her the neighborhood name “the Cookie Lady.” Doreen loved traveling with her family, looking for images of Saint Sebastian in every museum they visited. Sebastian is the patron saint for those who desire a saintly death, fitting for a woman who gave her body to science.

Most of the stories they tell me about their loved ones are universal, a comforting haze of good days and meals around dining-room tables. Paula Peltonovich’s father was not the only one to throw huge Sunday dinners every week; Janet Pizzi remembers her uncle, Michael Pizzi, doing the same with his brother, with whom he worked real estate well into his nineties.

More than one family remembers a loved one’s secret recipe: There’s Harvard-trained pediatrician William R. Buchanan’s famous carrot cake, which his granddaughters Lilli Pacher-King and Ellen Weiss refused to eat due to the natural aversion many children have to vegetables. (He made bowls of cream-cheese icing for them instead.) Amy and Jenny Gordon remember munching through countless batches of their mother Doreen Gordon’s macaroons, one of the confections that earned her the neighborhood name “the Cookie Lady.” Cookies “were her way of being known to other people, but also was a way of her saying to other people that she recognized them,” Amy recalls. “And I think they felt visible to her. And she was visible to them.” And Robyn D’Apolito and Nicole MacTaggart say their mother was famous for her pork fried rice.

Cathie Riordan says her father Frank would lose it if his name was in Rolling Stone; he was a musician who never stopped singing, even when he went to a care home. “He was just the average guy. And he was a good guy,” Cathie says. She adds of her father’s final donation: “He just wanted to do something big, because he hadn’t really done anything big in his life. Or at least, he didn’t feel like he had.”

Cathie Riordan’s father, Frank, donated his body to Harvard because he wanted to do something big with his life, to be remembered. He was a musician who hosted karaoke nights well into his sixties and never stopped singing, even when he went to a care home.

Then there’s Amber Haggstrom’s mom, Donna Pratt, a drag-racing car fanatic nicknamed “Miss Pyro.” “When I got my mom’s ashes I was so excited to have her back,” Haggstrom says, adding that she used to talk to them every morning. “I look at the ashes differently [after the Harvard news]. I feel like I’m almost losing that bond.”

Amber Haggstrom’s mom, Donna Pratt, was a thrillseeker: a drag-racing and firework fanatic nicknamed Miss Pyro. “When I got my mom’s ashes I was so excited to have her back,” Amber says, adding that she used to talk to them every morning. “I look at the ashes differently [after the Harvard news]. I feel like I’m almost losing that bond.”

That’s another thing these families have in common: Their memories are tainted by what happened to them after their loved ones died. And now, they’re trying their best to hold onto the people they’ve lost.

As I sit with Adele Mazzone’s daughters, D’Apolito and MacTaggart, on a muggy August afternoon around a flowery tablecloth, the sisters piece through the ephemera of their mother’s life. “I just think she’d be so disheartened to know the lack of prestige and integrity that Harvard now stands for,” D’Apolito says with a sigh, before turning back to a photo of her daughter, Brianna, and their mother standing in front of a slate-gray sea.

“Have you heard the poem ‘The Dash’?” D’Apolito asks. At 59, she’s got more than a decade on her younger half sister, but with her carefully styled blond hair and a brassy laugh, they seem close in age. “You get your birth date, your death date — but what’s in between? That’s the dash.” Mazzone’s dash is spread across that table. There are written recollections of the tragedies, like her brother and son, lost at young ages, and snapshots of the bright moments, the black-and-white photos of her apple-cheeked younger days, colorful snaps of more recent holidays.

“We have to relive this over and over. Envisioning my mom’s head being cut off. What did they do to her body? Why couldn’t I help her?” D’Apolito says, her eyes glazing with tears as she gazes distractedly at the bright blue and silver balloons bobbing by the mantel, detritus from her nephew’s birthday. “It’s not that someone who wasn’t a good person deserved that, but she really didn’t. Her ‘dash’ was pure goodness and giving.”

Update – Dec. 8th, 2023: Three days after the publication of this story, Harvard released its long-awaited independent review of the Anatomical Gift Program at Harvard Medical School. The review included several recommendations for the AGP going forward, including updating standard operating procedures, periodic review of donor consent policies, overhauled privacy and security measures, and suggestions for further staff training. They also announced that they have “appointed a task force chaired by HMS Dean for Medical Education Bernard Chang to review the panel’s recommendations and to develop an implementation plan in an expedient and thoughtful manner.” Moreover, family members were sent updated letters on Dec. 7th informing them of the review.